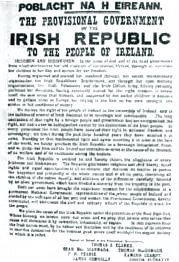

Easter 1916 and the Refracted Gaze of the Post-Colonialist

Mark Kaplan/Charlotte Street's excellent critique of cynically pragmatic, post-modern attempts at historical revisionism vis-a-vis Ireland's 1916 Rising [Easter 1916, or the politics of weather erosion] once again alerts us to the possibility that what passes for contemporary "realism" may often be little more than romanticism in disguise, the notion that myths and stereotypes are somehow rebutted by a simple recourse to "truth" and "hard realities", as if, like the incarcerated remains of Egyptian tombs, they have only to be exposed to the harsh glare of reality to disintegrate before our eyes.

Pointing to the trend among many eminent establishment historians towards an ahistorical, de-politicising analysis of Irish history, Charlotte Street quotes from an article by historian Roy Foster: 'Nowadays, the icons of 1916 are features on the Dublin tourist trail, which includes a "Rebel Tour" -even if the "bullet-holes" on the GPO's pillars have recently been declared to be nothing more than weather erosion'. [Erased by weather erosion, more likely, with some further sand-blasted rhetorical clarification and assistance from smug revisionists].

Pointing to the trend among many eminent establishment historians towards an ahistorical, de-politicising analysis of Irish history, Charlotte Street quotes from an article by historian Roy Foster: 'Nowadays, the icons of 1916 are features on the Dublin tourist trail, which includes a "Rebel Tour" -even if the "bullet-holes" on the GPO's pillars have recently been declared to be nothing more than weather erosion'. [Erased by weather erosion, more likely, with some further sand-blasted rhetorical clarification and assistance from smug revisionists].Of course, one of the principal casualties in any simplistic reduction - spiriting away - of political violence to "natural" or irrational forces is history. The new pomo post-historical breed of Forrest Gump "historians": Shit happens ... and life is like a box of chocolates. Such reductive "topographical realism" in Foster's naturalising of the GPO's spectral past serves to make it stand as a place apart, disengaged from all historical narrative, just another familiar landmark instead of constituting hallowed ground, imbued with the resonance of its political past.

Charlotte Street continues: "Were the rebels inspired to violent action by Romantic myth, or was a certain rhetoric enlisted (by some) in the service of a violence already deemed necessary?"

Quite literally, such rebels - as with everyone else - cannot step outside language or myth - they were already situated within an elaborate signifying system. Attitudes, both to violence and to the Irish then - as now - did not emerge newly-born but drew on a reservoir of ideas and images inherited from earlier historic periods; the associations of the Irish with violence had already enjoyed an extended career.

Quite literally, such rebels - as with everyone else - cannot step outside language or myth - they were already situated within an elaborate signifying system. Attitudes, both to violence and to the Irish then - as now - did not emerge newly-born but drew on a reservoir of ideas and images inherited from earlier historic periods; the associations of the Irish with violence had already enjoyed an extended career."For centuries, English writers, both eyewitnesses and more distant observers, remarked with professions of shock and horror upon the peculiarly cruel and anarchic nature of Irish violence. From Giraldus Cambrensis's chilling vision of a nation "cruel and bloodthirsty" and a country "barron of good things, replenished with actions of blood, murder, and loathsome outrage", to Barnaby Rich's assertion that "That which is hateful to the World besides is only beloved and embraced by the Irish, I mean civill warres and domesticall discentions," the English perspective was clearly drawn."===> Charles Townshend, Political Violence in Ireland (1983).

[Ah yes, the gaze of the colonialist: substitute "Iraqi" or "Haitian" or "Afghan" or "Iranian" or "Palestinian" or... for "Irish" above and then "Anglo-American" for "English" to bring matters fully up-to-date].

The pathologically diseased violent savages and terrorists have to be civilised by conquest, you see [humanitarian intervention etc]. And such "professions of shock and horror" did not simply represent the idiosyncratic attitudes of individual authors, of course, but were structurally connected to England's military and political domination of its neighbouring island. Cambrensis' notorious history of Ireland played a significant political role in justifying Henry II's conquest of Ireland on the grounds of its civilising influence while Barnaby Rich's A New Description of Ireland (1610) was only one of a number of Elizabethan commentaries designed to bolster the reconquest and plantation of Ireland initiated during the Tudor period. So successful were these ideas and writings, in fact, that by the 19th century "the major characteristics attributed to the Irish - indolence, superstition, dishonesty, and a propensity for violence" had, according to Ned Lebow, "remained prominent in the British image for over six hundred years."

The pathologically diseased violent savages and terrorists have to be civilised by conquest, you see [humanitarian intervention etc]. And such "professions of shock and horror" did not simply represent the idiosyncratic attitudes of individual authors, of course, but were structurally connected to England's military and political domination of its neighbouring island. Cambrensis' notorious history of Ireland played a significant political role in justifying Henry II's conquest of Ireland on the grounds of its civilising influence while Barnaby Rich's A New Description of Ireland (1610) was only one of a number of Elizabethan commentaries designed to bolster the reconquest and plantation of Ireland initiated during the Tudor period. So successful were these ideas and writings, in fact, that by the 19th century "the major characteristics attributed to the Irish - indolence, superstition, dishonesty, and a propensity for violence" had, according to Ned Lebow, "remained prominent in the British image for over six hundred years." "I'm a dead man!"

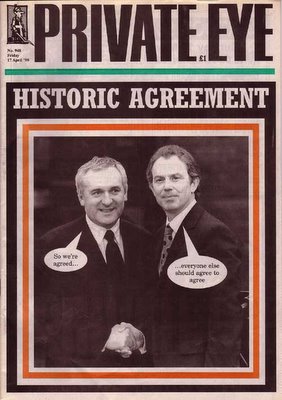

"I'm a dead man!"[In the 20th century, with the advent of cinematic images, matters continued: look at any of the films about the Irish "troubles" by numerous Anglo-American - and many Irish - film-makers who portrayed not simply the traditional inclination to imagine the Irish as violent but also the inability to provide any rational explanation for the occurence of violence - Carol Reed's Odd Man Out, David Lean's Ryan's Daughter, John Ford's The Informer, Basil Dearden's The Gentle Gunman, Shake Hands With The Devil, A Terrible Beauty, The Violent Enemy, Pat O'Connor's Cal, right up to the Neil Jordon trio Angel, The Crying Game, and Michael Collins, among numerous others].

But if derogatory images of the Irish succeeded in elevating military and economic exploitation to the status of a puritanical civilising mission they could also prompt the question of why the Irish should then prove so reluctant to accept the benefits of civilisation and resort to rebellion and uprising against their English benefactors. The answer, of course, was implicit in the phantasmatic designation of the Irish as violent. Violence, in this respect, was never to be accounted for in terms of a legitimate and proper ethical response to intolerable political and economic conditions but simply as a pseudo-genetic manifestation of the Irish "national character." By this token, the proclivity for violence was simply an inherent characteristic in the "nature", if not the blood, of Irish natives. Racism at its purest: The Subject Supposed To Kill ... Indeed, such racial conceptions enjoyed an obscene "scientific" dignity in the 19th century when the new theories of social Darwinism combined with the political hysteria over the Fenians to create a view of the Irish as a species of anthropoid ape, as the pages of Punch magazine eagerly attested. The Famine's Homo Sacer.

"Would it be about a bicycle?"===>Flann O'Brien

Michael Collins with his Strategic Weapon

Violence then, is attributed to fate or destiny on the one hand, or to the deficiencies of the Irish character. Both attitudes share a dizzying denial of social or political questions: it is only metaphysics, race, or madness, not history and politics, which offer an explanation of Irish violence, as with the First World's current relations with much of the Third World, as with Foster et al's agenda for Irish post-history.

But back to the GPO's enigmatic bullet holes:

The New, Improved GleamProg pomo GPO and environs, 2005.

"besides these more direct and documentary evidences, the history of every nation is enshrined in the national traditions, in the national music and song; much more, it is written in the public buildings that cover the face of the land. These, silent and in ruins, tell more eleoquently their tale ... This is the volume we are about to open."===>Thomas Burke [19th century preacher], Lectures on Faith and Fatherland.

Headstones may signify death but monuments, including the remains of round towers and monastic ruins, in nationalist iconography are signs of a new beginning, harbingers of a political and cultural awakening. It was precisely the invocation of an ancient Irish civilisation , exemplified by ruins and antiquities, which brought about a convergence of cultural nationalism and the separatist tradition which sought a complete break from Britain, outside the limited horizons of parliamentary democracy and reform. So if one kind of romanticism portrays Irish violence as some kind of pathological manifestation of raw nature, another form of romanticism, that espoused by cultural nationalism, sees landscape (and by extension violence) as a cultural creation, a mask which "covers the face of the land, " with the implication that cultural identity can no longer claim the permanence or authenticity of nature [itself contingent], but becomes a masquerade, a pursuit of artifice similar to the artistic process itself.

Headstones may signify death but monuments, including the remains of round towers and monastic ruins, in nationalist iconography are signs of a new beginning, harbingers of a political and cultural awakening. It was precisely the invocation of an ancient Irish civilisation , exemplified by ruins and antiquities, which brought about a convergence of cultural nationalism and the separatist tradition which sought a complete break from Britain, outside the limited horizons of parliamentary democracy and reform. So if one kind of romanticism portrays Irish violence as some kind of pathological manifestation of raw nature, another form of romanticism, that espoused by cultural nationalism, sees landscape (and by extension violence) as a cultural creation, a mask which "covers the face of the land, " with the implication that cultural identity can no longer claim the permanence or authenticity of nature [itself contingent], but becomes a masquerade, a pursuit of artifice similar to the artistic process itself.

This all suggests that it is not so much "realism" or the reality principle which offers a way out of the impasse of myth and romanticism, but rather a questioning of [politically determined] realism or any hegemonic mode of determination which seeks to shut down the bullets and their traces, the gap between image and reality.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home