Let Me Feel Your Lack: The New Malick

Wittgenstein asks a question, which sounds like the first line of a joke: 'How does one philosopher address another?' To which the unfunny and suitably perplexing riposte is: 'Take your time'. Ex-MIT lecturer on Heidegger, Terrence Malick (In 1969 he published his bilingual edition of Heidegger's Vom Wesen des Grundes as The Essence of Reasons)is evidently someone who takes his time.

Reverie, poetry, Phusis ... Haecceities: There is an intense calm at the heart of Malick's art, a calmness to his cinematic eye, a calmness that is also communicated by his films, that becomes the mood of his audience. In each of his films, one has the sense of things simply being looked at, just being what they are -- trees, water, birds, dogs, crocodiles, or whatever. Things simply are, and are not moulded to a human purpose. We watch things shining calmly, being as they are, in all the intricate evasions of 'as'. The camera can be pointed at those things to try and capture some grain or affluence of their ireality. The closing shot of The Thin Red Line presents the viewer with a coconut fallen onto the beach, against which a little water laps, and out of which has sprouted a long green shoot, connoting life, one imagines. The coconut simply is, it merely lies there remote from us and our intentions, suggesting Stevens's final poem, 'The Palm at the End of the Mind', the palm that simply persists regardless of the makings of 'human meaning'. Stevens concludes: 'The palm stands on the edge of space. The wind moves slowly in its branches'.

One also thinks of Wittgenstein's remark from the Tractatus: 'the eternal life is given to those who live in the present'.

Images of trees wrapped in vines, together with countless images of birds, in particular owls and parrots. These images are combined with the almost constant presence of natural sounds, of birdsong, of the wind in the Kunai grass, of animals moving in the undergrowth and the sound of water, both waves lapping on the beach and the flowing of the river.

"Nature might be viewed as a kind of *fatum* for Malick, an ineluctable power, a warring force that both frames human war but is utterly indifferent to human purposes and intentions. This beautiful indifference of nature can be linked to the depiction of nature elsewhere in Malick's work. For example, _Badlands_ is teeming with natural sounds and images: with birds, dogs, flowing water, the vast flatness of South Dakota, and the badlands of Montana, with its mountains in the distance -- and always remaining in the distance. _Days of Heaven_ is also heavily marked with natural sounds and exquisitely photographed images, with flowing river water, the wind moving in fields of ripening wheat and silhouetted human figures working in vast fields. Nature also possesses here an avenging power, when a plague of locusts descend on the fields and Sam Shepherd sets fire to an entire wheat-crop -- Nature is indeed cruel."===>Simon Critchly

[... and The Death of American Film Criticism]

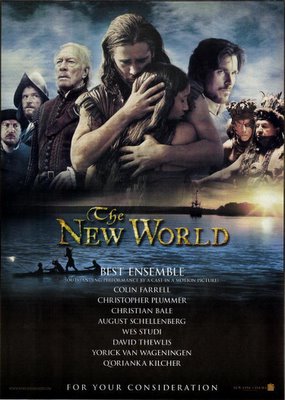

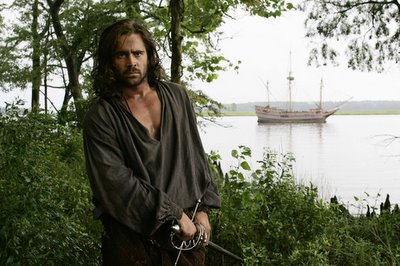

The subject matter is partly to blame: after four centuries of Anglo denial about the genocidal conquest of America, I was hoping for something a little more grown-up and educational about John Smith (Colin Farrell) and Pocahontas (the striking Q'Orianka Kilcher). Malick still has an eye for landscapes, but since Badlands (1973) his storytelling skill has atrophied, and he's now given to transcendental reveries, discontinuous editing, offscreen monologues, and a pie-eyed sense of awe. All these things can be defended, even celebrated, but I couldn't find my bearings. Jonathan Rosenbaum, The Chicago Reader.

The idealization of the native American existence in The New World, precolonization, is a pleasing fantasy but also timeworn and ahistorical. Surely someone as sophisticated as Malick - who once taught philosophy at MIT and was a Rhodes scholar - understands that he is putting forth a fabrication. Peter Rainer, Christian Science Monitor.

Malick's exalted visuals and isolated metaphysical epiphanies are ill-supported by a muddled, lurching narrative, resulting in a sprawling, unfocused account of an epochal historical moment. Todd McCarthy, Variety.

Well before The New World's two-and-one-half hours are up, Malick's tree-hugging reveries have become suffocating, no matter the unquestionable tastefulness with which they're rendered -- more painterly vistas, more Wagner (and a little Mozart, too), ravishing re-creations of 17th-century London. Surely, only a Philistine could find any fault with this, or believe, perchance, that Malick's famous poetic beauty had turned poetically fatal. Scott Foundas, LA Weekly.

Pocahontas catching us off-guard with an impromptu cartwheel isn't the knock-you-down brainstorm of Naomi Watts juggling for King Kong, but it's still deliciously inspired. Trouble is, the bit lasts two seconds, while the movie is a long "might have been" that's doomed to be buried in a flurry of strong late-year releases. Mike Clark, USA Today.

Malick's long, moody, diaphanous account of love and loss in 17th-century Jamestown--shot, more or less, on location--rarely achieves the symphonic grandeur it seeks. As an epic, it's monumentally slight. J. Hoberman, Village Voice.

This is like a Tony Scott movie on quaaludes: Words and pictures are matched up in counterintuitive ways, and although the cutting is much slower than in Scott's hyperactive showboating, it makes just about as much sense. The movie's leisureliness is aggressive; the picture is artfully designed to make you feel that if you're bored, it's your own damn fault. Stephanie Zacharek, Salon.com

If only the showmanship were equal to the scholarship. As beautiful as the film is (despite notable variations in the quality of the cinematography), it is also sluggish, underdramatized after that initial suspense, and for the most part emotionally remote. Joe Morgenstern, Wall Street Journal.

Myopic nutcases, the lot of 'em ...

"This dilemma is discernible down to the ambiguous way in which Tarkovsky uses the natural sounds of the environs; their status is ontologically undecidable, it is as if they were still part of the "spontaneous" texture of non-intentional natural sounds, and simultaneously already somehow "musical", displaying a deeper spiritual structuring principle. It seems as if Nature itself miraculously starts to speak, the confused and chaotic symphony of its murmurs imperceptibly passing over into Music proper. These magic moments, in which Nature itself seems to coincide with art, lend themselves, of course, to the obscurantist reading (the mystical Art of Spirit discernible in Nature itself), but also to the opposite, materialist reading (the genesis of Meaning out of natural contingency)."===>Zizek

2 Comments:

Great sampling of reviews -- I completely disagree with all of them, and I think they're very symptomatic of how films are viewed by American critics when they insult the concept of art as a commodity -- i.e. a movie like Malick's which is simultaneously long and subtle. I find it endlessly fascinating how so many critics were able to overlook or seal themselves off to moments in the film that I found intensely affecting and powerful, on the grounds that it was 'pretentious' i.e. not aware of its place

p.s. slant magazine (www.slantmagazine.com) has a great review by ed gonzalez

p.p.s. I really enjoy your blog

Much appreciated, traxus.

Thanks for the slant ref too. Another worthwhile review is Matt Zoller Seitz's at http://mattzollerseitz.blogspot.com/2006/01/there-is-only-thisall-else-is-unreal.html

Post a Comment

<< Home