The devil, probably ... Safety and Disease in Kapital [1]: Todd Haynes' [Safe]

[Anamorphic] Soundtrack of the Real

"You don't always notice it, but during a lot of the scenes in "Safe" there's a low-level hum on the soundtrack. This is not an audio flaw but a subtle effect: It suggests that malevolent machinery of some sort is always at work somewhere nearby. Air conditioning, perhaps, or electrical motors, or idling engines, sending gases and waste products into the air. The effect is to make the movie's environment quietly menacing."===>Roger Ebert

Michael Chion has already noted in his seminal study Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen (1994), that David Lynch is one of the directors that have liberated film sound from its long sleep of simply accompanying the images on-screen. Chion points out that Lynch is one of those who have developed the soundtrack into the direction of a "Sound Film - Worthy of the Name". In Lynch's Lost Highway, for instance, the outside (of the Madison house and marriage) literally starts to intrude the inside, and the threat is emphasized by the deep droning sounds (in a cinema with a good sound system, the spectators actually can feel this threat as an uncomfortable feeling in their stomachs ... already in Eraserhead, Lynch had made use of this device, the constant droning of a ship's engine underlying the whole movie).

Lacan comments on "this buzzing that people who are hallucinating so often depict ... this continuous murmur ... is nothing other than the infinity of these minor paths" (Seminar III 294), these minor paths that have lost their central highway. What is the deep droning sound underlying most of [Safe] and Lost Highway but this "continuous murmur?"

[Safe] Summary

"SAFE tells the story of Carol White, a Los Angeles housewife whose affluent environment turns against her in the form of an inexplicable illness. What begins as sudden allergic reactions to everyday chemicals, fragrances and fumes turns increasingly violent, transforming the laminated safety of Carol's existence into a terror of everyday life. When she is diagnosed with an immunity disorder called "Twentieth Century Disease," and sets off to New Mexico in search of treatment, Carol's journey turns inward. And, in the crisis of identity that results, "SAFE" reveals the ways in which disease infests our basic sense of who we are."===>Sony Pictures

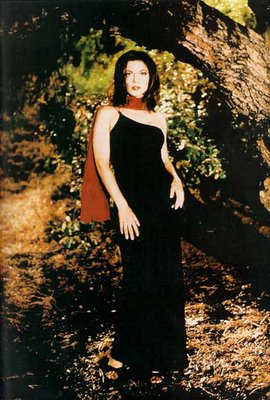

Set in the San Fernando Valley in 1987, the film recounts the life of a seemingly unremarkable homemaker, Carol White (played by Julianne Moore) who develops multiple chemical sensitivity, an allergic reaction to the visible and invisible toxins that plague her everyday life. Her environmental illness is not taken seriously by conventional medicine and psychotherapy, so she seeks solace in a fictional new-age/religious community in the desert called Wrenwood. Here, she strives for immunity from a world that has rejected her, and which she subsequently rejects.

The film has been seen by various critics as a metaphor of AIDS, while others have compared the film to 2001: A Space Odyssey in its use of austere visuals and its detached sense of place and time. Haynes adopts a minimalist style similar to Stanley Kubrick that is both neutral in judgment and tone, although there are many subtleties in the film that some careful viewers would contend suggest a viewpoint after all from Haynes.

The film has also had an unacknowledged influence on other films, most notably David Lynch. His Mulholland Drive uses similar credits, visuals and music to Safe, most notably in the first few minutes.===>Wikipedia

Post-industrial consumer Kapitalism as Disease

"Carol's alienation and self-delusion—her "[failure] to lay claim to the status of subject"—are signaled immediately when we see her have sex with her husband, the scene with which Haynes very pointedly begins his film. The camera records Carol's dissociation from the experience as she calmly and methodically rubs her husband's back as he grunts toward orgasm on top of her. The sterility of the scene is so haunting because it's evident that this is always how Carol and Greg have sex. But the scene is particularly painful to watch because it is also clear that Carol treats sex just as one of Marx's workers treats his or her job: as alienated labor, as something regularly to be got through.

[Safe] is not, as I have suggested, invested in whether or not Carol's illness is real, if what we mean by real is something like biochemical: her symptoms are not indicative of individual sickness but of the disease inherent in the modern industrial landscape. It is, however, Carol's attempt to escape that landscape to the new-agey self-help enclave in New Mexico that accounts for the film's most withering commentary on contemporary American culture.

The Wrenwood retreat, located "in the foothills of Albuquerque," is the epitome of a cultural discipline that spreads social disease as it purports to regulate our lives and cure our illnesses. The program at Wrenwood is a satire of self-help, twelve-step programs, full of vapid rhetorical questions ("What is your total load?") and ameliorative mottos: "We are safe, and all is well in our world"—hence the title of the film. Carol is coddled by her new friends, all of whom are disenfranchised, ostensibly as a result of their illnesses, which are not acknowledged by mainstream culture. The head of the program is Peter Dunning, who comes across with such smarmy earnestness that it may be easy to miss the film's scathing attack on all the cultural obsessions that Peter represents. The camera first exposes Peter's hypocrisy in a shot of the huge mansion he lives in. More aggressive is Haynes's deflation of Peter by repeatedly juxtaposing images of him (in one case just after he has pontificated about how "lucky" and "blessed" he is) with images of Lester, the broken-down, scarecrow-like Wrenwood "client," eviscerated by who-knows-what combination of physical and emotional trauma. Lester paces the sidelines of the film's action like a silent chorus.

Peter's mantra is that one can cure one's illness through self-love: "the person who hurt me the most is me." Peter counsels his Wrenwood clients, who convene at the retreat with various forms of unexplained, vague symptoms, that "nobody made you get sick, that the only person who can make you get sick is you, whatever the sickness." Peter continues, "If our immune system is damaged, it's because we have allowed it to be [through anger]." To make themselves better, Peter advises his clients "to remember [their] affirmations [and to love themselves more]." Peter's theme, according to the logic of the film, is a fairly monstrous emanation of American individualism, a notion underscored by the film's repeated reference to the power of the individual. In a television ad, Claire Fitzpatrick, Director of Wrenwood, says, "What I think makes us really unique is our emphasis on the individual"; Peter Dunning echoes the emphasis of Wrenwood in his opening speech about the centrality of "personal growth and self-realization"; toward the end of the film, the indoctrinated Carol White, a true tabula rasa, tells her husband (with her typical use of vague pronouns), "It's up to the individual." Because the cult of Wrenwood assumes that individuals have the power to heal themselves, the program sets these same individuals up for madness when they discover the limits of their own power to address the real sources of their illnesses."===> Julie Grossman, The Trouble with Carol: The Costs of Feeling Good in Todd Haynes's [Safe] and the American Cultural Landscape

"Environmental Disease"

Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (MCS)

"Multiple Chemical Sensitivity is now recognized as a legitimate disability by ten United States Government Agencies, as well as numerous state and local governments. MCS sufferers are now protected by the Americans with Disabilities Act. Although there is no cure, many patients do improve with appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Current research continues to provide professionals with greater understanding of this complex disorder."

---------------------------

"Writer/Director Todd Haynes first encountered environmental illness on a television human interest story concerned with a group of housewives who were developing extreme reactions to everyday chemicals. "They called it '20th Century Illness'," says Haynes, "because its sufferers seemed incapable of tolerating the very substances that pervade modern life. Ultimately they were forced to move into climate-controlled trailer homes and live the rest of their lives like the boy in the plastic bubble. What can I say? I was hooked."

"SAFE" is a stylish modern horror story where the enemy lurks in the very air we breathe. His bold visual style, by now a trademark to his fans, is set against a haunting musical score, evoking the horror that encroaches on us all.

Environmental illness is a condition which is the result of the body's reaction to myriad substances that have become a part of our environment, especially the 60,000 chemicals that are part of everyday life. These cause the breakdown of our immune and enzyme systems which results in a wide variety of symptoms. Traditional doctors dismiss the illness since its cause and effect are unproven but anecdotal evidence from individuals and the investigation of such substances in the workplace support the existence of chemical sensitivity.

"For me, living in New York City in the '90's has meant witnessing on a daily basis the disintegration of the American 20th century," says Haynes. "Poverty, homelessness, and the AIDS crisis have all contributed to a climate in which the notions of safety, immunity and survival have taken on a new meaning. And the more I learned about environmental illness, the more I was struck by its many parallels to AIDS. The difference is that environmental illness has a known origin -- chemicals. It is a disease that is imbedded in the very fabric of our material existence."

Production began on January 3, 1994 in California's San Fernando Valley, which is also the setting for the story. According to Haynes, "'SAFE' is purposefully set about as far outside the present day 'war zone' as I could imagine, in a world as protected and insulated as you could hope to find.

The central character, Carol White, is not your typical dramatic subject. Basically she's far too ordinary -- the kind of person you could speak to at a party and not recall the following day. But it is precisely this aspect of her that fascinated me most, exciting in me the urge to 'protagonize' her and prove her worthy of our attention and concern. For despite the film's cool depiction of the day-to-day routines that define Carol's life, we do not judge her. By the time the film has ended, our sympathy will be total."

Carol White is portrayed by Julianne Moore, who was immediately drawn to the part. "The script was exquisite -- the best I've ever read. Todd has a way of writing that is very specific, very direct and spare. It is rare to find such a talented director who is both literary and visual. It led to great communication -- Todd could show me a storyboard and I'd immediately know what he wanted. I also really felt that the character of Carol was someone that I understood. She felt so real to me. She wants so desperately to be safe. She wants everything to be safe, but she denies herself and is always fearful. When she finally encounters who she is, it is when she is the least safe, but it's a place she can't stay for very long and so she retreats, searching for safety in a place where she will never find it."

"Carol's understanding of herself is fully determined by the world in which she lives. Her increasing intolerance to her surroundings is experienced as a crisis of identity," comments Haynes. "If she can no longer drive on the freeway or perm her hair or buy new furniture then who is she? And more importantly, who are we? What kind of identification can we expect to make in a character with no identity?"

Until the film came along, Moore had no concept of environmental illness. But once she began her research, the reality of the disease could not be overlooked. "I watched several of videotaped studies in which children and adults were injected with a particular chemical and then monitored to record their reactions. It's amazing how varied the reactions can be. Some are quite extreme; in fact, Todd and I made a conscious decision not to use some of the reactions because they were so extreme they almost don't look real."

Playing the part, says Moore, was much scarier than she first thought it would be. "I lost ten pounds for the role and throughout the filming maintained an extremely strict diet. I felt myself drained of energy and I realized just how debilitating illness can be. After filming, it took me a while to shake the character. People often have a tendency to take their health, both physical and mental, for granted -- this role really offered me a chance to test the limits of how far an actress can go."

One ironic incident that occurred during the filming of "SAFE" was the earthquake that struck the Los Angeles area during the third week of production. "We would have aftershocks during a take," comments Moore. "It definitely was unsettling, but it also underscored everything we were trying to put across in the movie. I was watching news coverage of the quake and I saw a man who was shaking uncontrollably from shock. It was an image I couldn't put out of my mind and I ended up using his reaction for one of my own in a particularly climactic scene.

Moore continues: "I really hope that this film causes audiences to walk away thinking about their lives. It's so easy to be trapped by the way we live and, in Carol's case, she is trapped voluntarily. She has such a strong desire to be safe but she denies everything she is and could be.""===>Sony Pictures

------------

Horror Movie of the Soul

Safe has been described as a "horror movie of the soul", a description that director Todd Haynes relishes. California housewife Carol White seems to have it all in life: a wealthy husband and a beautiful house. The only thing she lacks is a strong personality: Carol seems timid and empty during all of her interactions with the world around her. At the beginning of the film, one would consider her to be more safe in life than just about anyone. That doesn't turn out to be the case. Starting with headaches and leading to a grand mal seizure, Carol becomes more and more sick, claiming that she's become sensitive to the common toxins in today's world: exhaust, fumes, aerosol spray. She pulls back from the sexual advances of her husband, and spends her nights alone by the TV, or wandering around the outside of her well-protected home like an animal in a cage. Her physician examines her, and can find nothing wrong. An allergist finds that she has an allergic reaction to milk, but explains that there is no treatment for that sort of allergic reaction. She sees a psychiatrist, who does nothing but make her nervous. In the hospital, Carol sees an infomercial for Wrenwood, a new-age retreat for those who are "environmentally ill", and leaves her husband and stepson to try and find salvation at this retreat: headed by a phony, grandstanding "sensitive individual" named Peter Dunning.

Summary written by http://www.imdb.com/SearchPlotWriters?David%20Eschatfische%20%7Besch@fische.com%7D

Todd Haynes' eerie medical thriller shows us that our environment has finally turned against us. Carol, a prototypical upper-middle class housewife, begins to complain of vague symptoms of illness. She "doesn't feel right," has unexplained headaches, congestion, a dry cough, nosebleeds, vomiting, and trouble breathing. Her family doctor treats her concerns dismissively and suggests a psychiatrist. Eventually, an allergist tells her that she has Environmental Illness. Her body is rebelling against the overload that her immune system has to deal with, as she is continually exposed to all of the chemicals that we inhale, ingest, and absorb daily. The pollution in our air, pesticides on our food, and toxins in our water, are collectively overwhelming her defenses. The ubiquitous sprays, creams, and emollients used to beautify have become deadly poisons to her. In essence, she has become allergic to the Twentieth Century. She sees Wrenwood as her only salvation, a New Age-y center run (quite profitably) by Peter, a cliched, easy-talking, demagogic guru. Unsettling and ambiguous, we are never sure about each character's hidden agenda, as they revolve around Carol, a timid, frightened pawn, overwhelmed by her condition.

Summary written by http://www.imdb.com/SearchPlotWriters?Tad%20Dibbern%20%7BDIBBERN_D@a1.mscf.upenn.edu%7D

===>IMDB

-----------------

"Safe is a masterpiece – if for no other reason than the discomforting feelings of claustrophobia in open space that its imagery so expertly generates. Its visuals have the sterility of Kubrick. They transform familiar suburban and natural landscapes into boxed-in prisons. This complements the story of Carol White (Julianne Moore), a housewife in 1987 California who becomes allergic to her environment. Her disease baffles everyone – her doctors, her husband – and she finally goes to the Wrenwood Center, a New Age health retreat, where she hopes to recover. A childlike viewpoint is evident throughout Safe. Carol’s house is filled with possessions and pictures accumulated over a lifetime that constantly haunt her with history. Haynes pans over a family picture display at one point, and it is frightening to see the change in Carol’s expression from early childhood to early adulthood. The smiles of a toddler Carol are juxtaposed with the blank, passive expression of a high school photo, suggesting that this bird has been trapped for years in a gilded cage, completely unawares. Carol is also stepmother to her husband’s son – a metaphor of disconnection from the people around her, and nicely played out in a later scene at Wrenwood when the young son is framed at the far right of the image away from Carol and her husband as if separated by an immense gap. We might call this an illustration of Carol’s loss of innocence, but Haynes doesn’t seem to wholly believe in the innocence of children. Rather, he suggests there are worlds of difference between adult and child – each stage has its own rules of conduct and behavior, and yet it is inevitable that the two sides will confront each other. In Haynes’ work, this is oftentimes a cataclysmic meeting of the minds – from the intentionally mangled Barbie dolls in Superstar, to the child’s murder of his father in Poison, to Carol’s physical and emotional journey in Safe. Indeed, Carol appears to regress, over the course of the film, to a childlike state. Sealing herself in a sterile, white igloo at the end of the film, Carol looks in the mirror, past herself and into the audience, and says, "I love you." In this moment she is born again, but at the expense of the physical trappings of humanity. She is now a child locked in a protective womb, and we regard her both as alien and compatriot. The disease gives Carol identity, and she passes this onto us, infects us with her own truth. It’s as powerful an image as that which ends Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), albeit one whose aims are even more ambiguous and unsettling for being confined to a recognizable, earthly plain."===>Keith Uhlich in Senses of Cinema

"SAFE. "I love you... I really love you... I love you..." This is Carol White (Julianne Moore) addressing her image in the mirror, or in the camera lens, at the end of Todd Haynes' 1995 film Safe. The words are halting and uncertain; Carol is trying too hard to convince herself that all is well. Her ravaged face, in a rare close-up, occupies the center of the screen. She looks tired. A reddish blotch covers much of her forehead. At least she's not coughing any more, or losing her breath, or having convulsions. But she still needs frequent hits from the oxygen tank she carries around everywhere. Carol is environmentally sensitive. She falls ill at the slightest trace of any of the numerous chemicals that pervade our homes, our workplaces, our shopping malls, and even the air we breathe. Her body can no longer tolerate the artificial toxins--or for that matter, the artificial culture--of white, bourgeois Southern California. She doesn't really know what's wrong--at first, she thinks it's stress--and neither do her doctors. But she feels that something is out of whack; her body won't let her forget it. Carol, it seems, is "allergic to the twentieth century." Somehow, she doesn't fit in. We see her mostly in long shots, framed within expensive, sterile interiors. She seems baffled and disoriented in these vast suburban spaces: whether she's driving on the freeway, running errands at the mall, or squriming on the psychiatrist's couch. Her San Fernando Valley home is lavish, but uninviting; you wouldn't feel comfortable sitting on those color-coordinated sofas, or wandering from outsized room to outsized room. These places are so alien, so out of scale, so inimical to the flesh. Carol is literally suffocated by them. She finds herself puking, or thrashing about, or coughing uncontrollably: it's the only way her body has to expel their poisons. The violence of her symptoms is her one true contact with the world. There must be more to life than aerobics and beauty salons and baby showers. Her body feels this, even if her conscious mind does not. She has to find a way out; a physical breakdown is her means of escape. She abandons home and family, in the second half of the film, to take refuge in the "chemical-free zone" of Wrenwood, a healing facility out in the desert. Now she's alone in her safe house, a spare, windowless, porcelain-lined cell. From the outside it looks sort of like an oversized white egg. Inside, it's severely minimal and constricted. The furnishings are spartan, the walls close at hand. No toxins can get in, and nothing whatsoever can get out. Is such close confinement the price she must pay for health? Convalescing, she just wants to retreat from the whole world. But how far must she go, before she feels safe? The desert air is clean and wholesome, but never quite enough. Even the fumes from a passing truck put her in a panic. The only things she can call her own are her awkwardness, uncertainty, and fear. These are the very points through which her allegiance can be engaged. For Wrenwood is really a New Age cult, run by the creepy guru Peter Dunning (Peter Friedman). He encourages Carol to look inward, into herself. Her selfhood is as carefully nourished in Wrenwood as it was denied at home. You yourself are responsible for your illness, Peter tells her. If you got sick, it's because on some level you chose to. If you want to get well, shut your eyes and ears to everything from outside. Purge away those negative feelings, and give yourself to love. Learn to cherish and love yourself, and everything will be fine. Life at Wrenwood is a continual training in selfhood. It goes well beyond what's offered in infomercials and self-help videos and 12-step programs. Haynes shows us the process completely deadpan: the group therapy sessions, the strategic displays of sympathy, the earnest exhortations, the communal dinners. If the first half of the film contemplated the horrors of outer, suburban space, the second half renders visible something much harder to see: the real estate development, as it were, of inner, psychological space. Almost nothing overtly happens in this part of the film. Only, step by step, Carol is cajoled into assuming a new identity. The New Age gives her a soul to match her white suburban body. Self-esteem is the redemption offered to wayward Stepford Wives. Carol's ailing flesh will never be healed, but it's as if she no longer cared. Space contracts to that last shot of just her face in the mirror. We are left uneasily suspended between hope and desolation. For what kind of response is a reflection capable of? No matter how much Carol loves that face, it will never love her back. She has only gotten out of one trap by falling into another. Her timid attempt to escape has left her stranded in another impasse."===>Shaviro

"What am I, then? Question asked by Julianne Moore's character in Todd Haynes's Safe. Asked by her body and its allergies. As if her body were that diremption of the inner and the outer. Who am I? And then to the mirror at the end, tentatively, she says I love you. But the you now undetermined, open. Words spoken to the mirror as it reflects back what she is not."===>Spurious

"Safe has an errie, sinister quality to it. I half expected a Lynchian boogie man to appear and reveal this vision of the world that Haynes was showing us was a mask hinting at some evil reality. There is no such relief or escape. The materialistic, artificial, indifferent world is suffocating Carol mentally, physically, spirtually. He environment is cluttered with expensive things. The pressures of modern living are breaking her.Her health deteriorates. She flees to a new age health farm to heal. But she finds another soulless extreme. She keeps getting worse. The fragility of people faced with the alienation of our modern world is one thing I came away with. This is an elusive film. It's hard to put your finger on a single defining theme. Julianne Moore is brilliant as the vulnerable, timid house wife. It has a slow mesmerising style that is indeed comparable to Kubrick." ===>Matthew at Rotten Tomatoes

"A superbly ditzy Julianne Moore plays Carol White, a San Fernando Valley housewife whose closeted middle-class existence results in multiple allergies, a nervous breakdown and her eventual absorption into a 'New Age' retreat for the socially dysfunctional. Haynes' earlier films include a life of Karen Carpenter featuring animated Bardie Dolls and the stylistically splintered Poison. Here, he again beats his own path in terms of genre and tone, but his stance is so coolly detached that one's left at the end in a state of deliberate uncertainty about whether Carol quits or finds a 'safe' life. The ironic handling of decor and characterisation builds an eerie portrait of the blissed-out West Coast bourgeoisie at their most brainwashed."===>Time Out Film Guide

"Safe came up in a millennial Village Voice poll of critics as the best film of the nineties, and it would be difficult to expand upon the many well-deserved superlatives that have been rightfully heaped upon it. One doesn't feel comfortable calling it a mere "movie;" it's a great work of art in the medium of cinema, brilliantly conceived and executed, perfect in every aspect, from Alex Nepomniaschy's cinematography to Ed Tomney's music to the graceful, un-showy performances (Moore gives an incredibly moving, almost inconceivably generous anti-star turn as Carol White, a demure woman who avoids any expression of emotion or opinion)... It's not that Haynes's work doesn't fit into tradition(s) of sorts; only on rare occasions has he mentioned Safe without citing the influence of Chantal Ackerman's 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, in which the minutiae of suburban housewifery are studied in practically real time, or Kubrick's 2001, in which the "subjects" are also dwarfed by their environment, a daunting milieu of ostensible advancement and progress. "===>Christopher McQuain in The Film Journal

"I always ask people what they think happened to Carol because it tells me a lot about them and how they view her predicament. Personally, I think Carol doesn't get any better-- that she only gets worse. She's just gone to another place where they're going to tell her who she is, and that will continue to make her sick."===>Julianne Moore, on what she believed happened to her Carol character at the end of Safe.

ONE: Carol White anticipates the delivery of her new blue-toned couch. Anyone would. But when she arrives home to find that a black one has infiltrated her habitat in the Valley, she gasps as if having just found her child bleeding on the floor. After all, it is not the one she had ordered, and her life is now out of balance.

TWO: Some time later, Carol guides delivery men into her living room and, having placed the teal couch in its proper place, they all stand still and silent, staring in various directions, camera resting on them as all involved (including the audience) wait for a cut. Perhaps Carol is taking the moment to recover from her setback, for now all is right in her world. What is for certain, though, is that she is waiting, waiting for something to do.

This is a very telling pair of scenes from Todd Haynes' Safe, a film that exhibits the physical and emotional fragility of its main character, a fragility formed by the shallow and lifeless world that she occupies--that of her San Fernando Valley circa 1987. Carol (Julianne Moore) is a suburban housewife, spending her days tending her gardens, socializing with her fluffy friends, satisfying her husbands needs and aerobicizing (although [android?] she never breaks a sweat). Julianne Moore glides through her role with a tentative grace, her pale complexion and delicate features working hand in hand with a hesitant and unassertive demeanor. She is the perfect victim-heroine for the director/writer's subject, and he seems both critical and sympathetic of her, effectively walking the line between the two.

Haynes places her within wide-framed, aesthetically cold, muted and barren interiors, keeping the camera at a distance so as to isolate the film's human subject. Safe's first act pulses and literally drones along, with television emissions and gentle, mechanized hums filling the soundtrack. The effect is unmistakably 2001esque (The New York Times accidentally described the film as taking place in the future), and Haynes credits Kubrick's 1968 project as an influence. And although at times Carol's life seems to be playing out inside some sort of machine, the HAL 9000 that controls the fate of 2001's heroes does not exist in the San Fernando Valley. This heroine's fate lies in the hands of another human creation, her upper class suburban sprawl.

Suburban life in general and suburban Los Angeles specifically has had its place contemporary films. But whereas Tim Burton's Edward Scissorhands satirizes the suburban world as pure caricature, with its childlike color coded sets, and Spielberg's suburban California is a place where magical things can happen, Safe's San Fernando Valley offers a somber and ultimately bleak outlook on the state of human beings' "privileged" habitats. This slice of life has gone numb from segregated isolation and lack of stimulating personal contact (even Carol's "intimate" moments of lovemaking are spent staring upward, emotionless, assisting along her husbands pumps and groans.) These influences comprise the disease that has broken down Carol's immunity system; she is, as the bulletin board flyer states, "allergic to the 20th Century."

It is no wonder, then, that Carol begins feeling weak and sick for reasons that neither she nor her husband can understand, and that her doctors will not accept. From a hospital bed, she views a television commercial for Wrenwood, a New-Age compound in the Arizona desert and decides to give this healing resort a try. Here she falls under the aid of group guru Peter Dunning (played with a dry, subtle subversion by Peter Friedman), and begins her "healing" process. To his approximately 20 understudies, Dunning preaches the necessity of gentleness, understanding, and love, and though he adds a bit too much sugar to the recipe, these are facts difficult to argue. His questionable thesis, though, begins to reveal itself as he proclaims "I have stopped reading the newspapers. I have stopped watching the news on television." Dunning feels, in addition to looking inward, that completely isolating himself (themselves) from the outside world is a solution to their suffering. In doing this, he is replicating the very system that has destroyed many of these people. By turning his back on the world, he has dismissed not only its pains, but also its pleasures, created a false sense of well being, halted inoculation and perpetuated the "disease." [Haynes may be accused of rallying behind this point of view if it were not for the visual revelation of Dunnings ostentatious mansion, sitting on the hill (recalling, from Schindler's List, Camp Commander Goeth's gunning quarters), overlooking his subjects.]

Carol's husband visits, and though she claims that she has improved during her "temporary" stay at Wrenwood, he cannot even gain a kiss goodbye without eliciting a physical reaction: "maybe it's your cologne....I'm not wearing cologne!" Carol has "progressed" to the point where she cannot consummate her most intimate relationship. From this moment on, her fate is sealed, and after her birthday party celebration in which she gives a pathetically sad, "I fit in" speech thanking her fellow Wrenwooders for helping her so, she retreats to her white bubble-pod, stares into her mirror, and proclaims "I love you." All the while, the anonymous growth-boil-scab that has become more readily apparent on her forehead, grows."===>Kirk Hostetter , 24fps Fanzine

Kubrick's 2001 as precurser to [Safe]

"There's clearly no better time than now to reflect on the degree to which Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey anticipated the future. How far does the world of 2001 resemble the world of 2001?

An intriguing essay by Mark Crispin Miller published in Sight and Sound in 1994, suggests that we do live in 2001's world, but not in the way that those watching the film when it was released in 1968 might have imagined. It was not 2001's simulation of the experience of outer space, Miller argues, that made the film prescient; no, it was Kubrick's vision of commodification and control that was his most important apprehension of the (then) future. For Miller, Dr Floyd, the US scientist charged with investigating the anomalous 'monolith', belongs to a totally commodified, totally controlled environment, an environment that, in 1968, was still a distant enough prospect to provoke horror in the film's viewers. According to Miller:

The world of Dr Floyd (like the new dorm mall or hospital) is a world absolutely managed - the force controlling it discreetly advertised by the US flag with which the scientist often shares the frame throughout his 'excel lent speech' at Clavius [the US moonbase], and also by the corporate logos -'Hilton', 'Howard Johns 'Bell'- that appear throughout the space station.

Those who experienced 2001 back in the 1960s might feel, now, that they have experienced late capitalism twice, the first time as a film, the second as a banalized everyday reality. But what was once satiric prophecy is now blank realism, devoid of any 'ulterior motives', devoid, in many important respects, of any interest. "2001 could not [now] exert its original satiric impact because the mediated 'future' it envisions is now 'our' present, and therefore unremarkable. Whereas audiences back then would often giggle (uneasily, perhaps) at the sight of say, Howard Johnson up there in the heavens, Miller writes:

today's viewers would fail to see the joke, or any problem, now that the corporate logo appears en masse not just wherever films might show, but also in the films themselves, whose atmosphere nowadays is peculiarly hospitable to the costly ensign of the big brand name. We might discern the all-important difference between what was and what now is by comparing Kubrick's sardonic use of 'Bell' and 'Hilton' with the many outright corporate plugs crammed frankly into MGM's appalling 'sequel' 2010, released in 1983.... '2010 is a case of how product placement in the movies are becoming a springboard for joint promotions used to market films,' exulted Advertising Age before the film's release, noting the elaborate plugs for Pan-Am, Sheraton Hotels, Apple Computer, Anheuser-Busch and Omni magazine.

The shift Miller identifies between how audiences responded to 2001 in 1968 and how we would expect them to react 'now' - is a near-perfect illustration of Frederic Jameson's theses about consumer culture and multinational capitalism. For Jameson, famously, the culture of consumer (or 'late') capitalism makes 'satire' impossible, because satire depends upon the possibility of a - transcendent and critical - space between cultural objects and what they 'represent', a possibility that no longer exists. The critical possibilities supposedly available to the modernist creator-author have collapsed in a postmodernist 'total environment' where the illusion of a separate aesthetic and political realm beyond capital is no longer persuasive: a film, we now happily accept, is just as much a commodity as is Coca Cola. So although 2001 is 'about' the "new and historically original penetration and colonisation of Nature and the Unconscious" that Jameson thinks is characteristic of the culture of 'multinational capitalism', Kubrick's film now seems oddly dated, precisely because it imagines that commodification can be resisted, rather than merely exemplified. And the banality of commodfication retrospectively swallows up the film and its creator, too. While Kubrick no doubt remained, up to his death, the very image of the modernist creator, the name 'Stanley Kubrick' is now a brand name, a commodity, whose connotations - even when they include a certain disdain for 'the market' are highly marketable ... ."===>Mark Fisher, SF Capital

"In place of Sartre's existentially-tormented man, or Foucault's disciplined subject, we are presented now with what Burroughs and Deleuze identify as the agent/victim of Control. As Miller recognises, Kubrick's Dr Floyd is just such a 'control addict', whose "impulse to retreat from nature, to lead a 'life' of perfect safety, regularity and order in some exalted high-tech cell, and to stay forever on the job, solacing oneself from time to time with mere images of some beloved other, is ... the fundamental psychic cause of advertising.""===>Mark Crispin Miller, 2001: A Cold Descent

-------------------

[Safe] as Critique of Leftist inter-passivity and New Ageism

"Todd Haynes, director of Sundance Grand Prize Winner Poison and the underground classic Superstar, was inspired to make his latest feature, Safe, by his visceral response to New Age recovery therapists who tell the physically ill that they have made themselves sick, that they are responsible for their own suffering.

Carol White, played superbly by Julianne Moore, is an archetypally banal homemaker in the San Fernando Valley who one day gets sick and never gets well. Her doom is first her own unique physical condition. But her "action" is to be exposed to two kinds of discourse about illness. One is a conventional discourse that tells her that since what's wrong with her can't be diagnosed, it must not really exist. The other, found at a New Age-styled retreat called Wrenwood, is an unconventional remedy that acknowledges her condition with a certain sentimental empathy but which further alienates her from the social reality around her, rendering her even more incapable of taking significant action in her own defense.

Safe is a political film that almost never directly mentions political issues, a horror film without any monsters, special effects, or killings, and a relationship film without any regular psychological inflection. It is on the surface an utterly traditional narrative film, but one which is also secretly a work of difficult abstractness. Working with a bigger budget and trying to reach a larger audience, Haynes has wound up making his most demanding and elaborate film yet."===>Larry Gross talks with Safe's Todd Haynes

Larry Gross: I came across something today in a 1949 book of Maurice Blanchot where he's trying to tease at the relationship between Surrealist literature and its ambition to be political: "And we can also see that the most uncommitted literature is also the most committed because it knows that claim to be free in a society that is not free is to accept responsibility for the constraints of that society and especially to accept the mystification of the word "freedom" by which society bides its intentions." He's talking about the fact that Surrealism attempts to be revolutionary even while moving completely away from direct, explicit engagement with social and political questions. It tries to produce the image of freedom and at the same time reveal the mechanisms by which freedom is constrained. That sounds to me to be similar to the political discourse in Safe. And what's interesting about it is there's no explicit political discourse in the film. Do you worry that people won't understand that there'a a political meaning to the film?

Todd Haynes: It's something I've been thinking about since Sundance, absolutely. It's disappointing to me because what Poison taught me was that a lot of people out there are eager to see different kinds of films. They wanted to be challenged. Not necessarily art-film goers - people a couple of steps outside that world still want to be engaged and challenged by film and aren't given the chance most of the time. It's pretty clear to me what's going on in Safe at the end. It's a pretty unambiguous condemnation of a New Age answer to life's problems.

LG: I think it's more than that. I think this is the one movie that describes the complete collapse of left-wing oppositional culture in this country.

TH: That's so interesting.

LG: Because it's made clearly sympathetically to the criticism of conventional institutions that left-wing causes are supposed to undertake.

TH: And it targets left-wing audiences and left-wing expectations in a fairly nasty way. [In the Wrenwood section of the film,] the first time you see the black character, Susan, you think, "Oh, this has gotta be a cool place," and then you see Peter, who is described as having AIDS and you think, "Oh, he's gotta be cool, it goes without saying, Todd Haynes is a gay filmmaker." So it's like all these things mislead your expectations. People of color, minorities, people from backgrounds different from Carol's in the film keep prodding you toward thinking that there's going to be some political rhetoric or some revolution that will tell you what's right and what's wrong and it continues to trip you up till the end.

LG: You could've addressed it more directly. You chose not to.

TH: I realized before we started shooting how much of a critique of leftism this film is. What did initiate it was a series of personal questions about recovery treatments and therapies in relation to AIDS. Why so many gay men seemed to be drawn to people like Louise Hay in the '80s, people who were literally telling them that they made themselves sick, that they could make themselves well if they simply learned how to love themselves. I didn't really care about the Lousie Hays of the world, the Marianne Williamsons. But, ultimately, what was it in people who were ill that made them feel better being told that they were culpable for their own illness than facing the inevitable chaos of a terminal illness?

LG: It's an attempt to sort of escape the catastrophe of a complete absence of genuine political power. It's about making yourself comfortable with powerlessness.

TH: I guess that's it, but why is there such a complete and total replacement of what was once and outward-looking critique of society by this notion of a transcendent self that can solve all our problems?

LG: I think it's a persistent strain in the progressive side of American culture that leaps off the tracks and becomes a weird individualistic-type mysticism. It's very Thoreau and Emerson in a different way. People who at one stage in their career are critical of a lot of American capitalist society and then move in some strange pre-Nietzchean way off the tracks into some elevation of the private individual person as the only incorruptible unit left. Let's talk about Wrenwood a little more because it's obviously a source of tremendous controversy in the film. I'm going out on a limb and say your characterization of the San Fernando Valley applies to Wrenwood. I don't see you completely demolishing Wrenwood as an ideological delusion. There's tremendous human sympathy for the people of Wrenwood. Peter, with all of his authoritarian-totalitarian aspects, has another side. He's also a human being who is trying to do the right thing.

TH: I think part of that is a ploy to paint him very carefully and more sensitively at the beginning so that you this might be the answer for Carol. The other part of that is due to Peter Friedman's performance because you really believe that the character is real and not a narrative device. It was just a really subtle and intelligent performance. During the writing, I felt that the least interesting thing you can do with New Age stuff is totally accept it or totally dismiss it. So I really tried to look at it. But ultimately, there are certain phrases and markers that I don't have any ambivalence toward whatsoever. Like saying, "I've stopped reading the newspaper, I've stopped watching the news on TV." I can't get past it. There's another place in the film where I wanted to start tightening the screws. When Peter goes around circle and, one by one, beats these poor people down into this self-confession of their pure culpability for their illness, and thanks them afterwards as they break into tears. It's an assembly line, packing these people down into their little holes. That to me is not a very subtle depiction of New Age thinking, as far as I'm concerned, and yet I still think people want something more, you know, Jean-Claude van Damme breaking through the screen and shooting them all down with a machine gun. Then you know it's bad.

LG: You've been the object of criticism because certain people think you agree with this character.

TH: That's true. But now we've added a shot of Peter's house on the hill that was not in at Sundance. [After the Sundance Screening, Haynes re-inserted a shot of Peter's opulent home to clue the audience into the character's hypocrisy.]

LG: And you think that helps locate Peter?

TH: I do think it helps clarify him.

LG: What does Carol's relationship to Chris [a fellow resident of Wrenwood played by James LeGros] mean to you in the movie? Is itone of those things dangled in front of the audience as a kind of way out that can't be a way out?

TH: I guess I wanted it to be another red herring, where you'd think, okay there will be a romantic resolution and Wrenwood has all the potential for perfect closure and happiness. Instead, one by one, these hopes fall away and you're left with Carol and Chris in this sort of platonic day-camp friendship. I didn't write him as a gay character. Did you think he was?

LG: didn't know. It crossed my mind.

TH: That's great. Julianne told me later that [actor James LeGros] had decided that he was Peter's boyfriend. Julianne also felt very strongly that there should be no esxual magnetism between Chris and the Carol character.

LG: Wrenwood to me is a kind of mirror image of the valley. Were you conscious of trying to construct it visually so ir referred back to the valley?

TH: Did you see that? I didn't go overboard in doing it and sometimes I think, "Oh I should've made that a little more clear." That really is what I wanted to convey.

LG: Leaving the world of the film for just a second, do you ever feel ambivalent about making a film that's this pessimistic? Is somebody watching the film gonna say, "I should give up, there's no hope" or do the opposite and develop a new political awareness at the end?

TH: If the film is constructed with any kind of target, it targets that unbelievably persistent "warm feeling" in Hollywood filmmaking that every clumsy narrative is moving towards achieving in the last five minutes, where the central character is really the director, is really the writer, is really you and we're all the guys and we're all in it together and we get the girl and feels so good about life. It's so upsetting to me, I can't tell you. It's such a fucking lie and that's what i wanted to dispel in most of the films I've made. So, to feel really sad for one fragile woman for two hours...If anything, what Safe does is refute the sense we make of identity, the sense we make of cures, the sense we make of notions of wellness and health. I think its most hopeful place is in the middle of the film. [Carol] gets angry in the hospital and says, "It's the chemicals that did it to me." There's something about saying, "It's the chemicals," which up to that point, until you know that it may be the chemicals, all you can think of is, "It's her. She's a mess. It's in her head. She's a nut. She's a fruitcake"

Reviews of [Safe]

Julie Grossman, The Trouble with Carol: The Costs of Feeling Good in Todd Haynes's [Safe] and the American Cultural Landscape

Roger Ebert

Larry Gross talks with Safe's Todd Haynes

Todd Haynes on the soundtrack of [Safe]

Christopher Null

Rita Kempley

Stephen Brody

Kirk Hostetter , 24fps Fanzine

R.C. from Time magazine, 1995

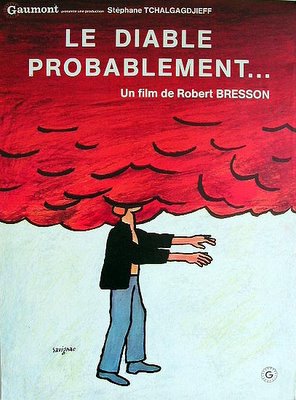

Le Diable Probablement

Robert Bresson's 1977 film serves as a compelling contrast to Haynes' [Safe], with the protagonist choosing active nihilism (versus the passive nihilism of [Safe]): suicide.

"For myself, there is something which makes suicide possible - not even possible but absolutely necessary: it is the vision of the void, the feeling of void which is impossible to bear."- Robert Bresson

Plot summary: The story unfolds of Charles, a young man living in Paris. He wants more from life than the glib, superficial truths and material things that are on offer to him. He reaches out to his family and friends and psychiatrist to provide him with the great answers in life. But his spiritual deliverance remains beyond his grasp until he reaches a bizarre arrangement with a fellow hippie.

A beautifully moving tale of a young soul in torment, The Devil, Probably follows Charles and his quartet of friends, all in revolt against the pollution of an industrialized consumer society. Alberte leaves Michel, an idealistic activist whom she loves, to care for the melancholy Charles. Charles, however, finds temporary solace in the arms of Edwige. Despite the concern of his friends, Charles is unable to find redemption in revolution, the church, psychoanalysis, or even love. He spirals further and further into a state of inactivity, until one night, among the ghosts at the famous Pere Lachaise cemetery, he makes a desperate bargain with a junkie friend. A daring portrait of "after the revolution" disillusionment, The Devil, Probably "expresses the malaise of our time more profoundly and more magnificently than any work of art in any medium" (Andrew Sarris, Village Voice).

"Robert Bresson's The Devil, Probably, is a powerful cry of despair aimed at a world without values. In this 1977 film Charles, (Antoine Monnier) a young man of about twenty, rebels against society's destruction of the planet and arranges his own death as a protest. What does he want? "I ask nothing", he says, " I lay claim to nothing…If I did anything, then I'd be useful in a world that disgusts me". Bresson describes his work as "a film about the evils of money, a source of great evil in the world whether for unnecessary armaments or the senseless pollution of the environment." The title comes from a scene on a bus when Charles says to his travelling companion that "Governments are short sighted," and other passengers join in the discussion. One says not to blame governments, "it's the masses who determine events. Someone asks, "So who is it that makes a mockery of humanity? Who's leading us by the nose?" And the first passenger replies with unmistakable irony, "The Devil, probably," and then the bus crashes amidst the cacophony of honking horns.

The film begins and ends in darkness and light is meagre throughout. One is not used to colour in a Bresson film but here colour is almost non-existent and Paris has never looked colder or bleaker. After an illuminated boat pierces the darkness and drifts along the Seine, two newspaper articles are flashed on the screen. Eliminating any suspense, the newspapers announce the death of a young man in Paris, one article says it is a suicide, the other a murder. We then go back six months. The main protagonist, Charles, joins his friends in a meeting about the environment. All of them watch videos of man polluting the environment and scenes of nuclear destruction. They play bongo drums and talk about religion but to no apparent purpose. Each scene is brief and does not last long enough to involve us emotionally.

Charles looks like a typical College student but has the air of insufferable superiority that can only come through righteousness. Physically, he is slender and quite handsome and one does not expect to see an attractive actor as the lead in a Bresson film. He has a nucleus of friends, Michel, Alberte, Eddwige who are concerned about him but he gives little in return, showing no outward emotion and all seem to move about in a catatonic state. Concerned about where Charles seems to be headed, his friends arrange for him to visit a psychiatrist but he tells Dr. Mime (Regis Hanrion) that his problem is only that he "sees things too clearly". He reads from a crumpled brochure in his pocket, telling the doctor what he would lose if he lost his life: family planning, package holidays, cultural, sporting, linguistic, the cultivated man's library, all sports sickness, credit cards, and so forth. The young man says that he is not depressed, that he just wants "the right to be myself. Not to be forced to give up wanting more . . . to replace true desires with false ones based on statistics". In a moment of humour rare for Bresson, the doctor tells Charles that it if he was spanked as a child it is possibly the cause of his feeling crushed by society and asks him, "When it's over, do you see yourself as a martyr?" The reply: "Only an amateur."

On his way to his ultimate protest, the young man hears the sound of a sublime Mozart piano concerto coming from an open window. He stops to listen as if trying to find the source of grace but is denied. When he sees that the music is only coming from a television set, he continues his journey to its inevitable conclusion. The climax, unlike other Bresson films that engender a feeling of spiritual lightness, left me uninvolved, more depressed than moved. When Charles begins to talk about his lack of sublime feelings, he is stopped suddenly in the middle of a sentence, unable to explain to the world why he thinks he has run out of options. In the end he gets to be right…dead right. His death, however voluptuous, does not clean up any toxic waste, save the felling of a single tree, or protect the life of one baby seal."===>Howard Schumann

Resolving the Dilemmas, the Symbolic Deaths of Carol and Charles in [Safe] and The Devil, Probably

In The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis Lacan argues that there is a dilemma of justified paranoia which is fundamental to the human subject (at least the modern human subject, that is). Each of us must avoid two positions, either of which means we lose our identity, suffer a symbolic death. On the one hand there is the choice made by Polyneices [ homologous to Charles in The Devil, Probably] to oppose the symbolic order, to stand outside its rules and operations, the penalty for which is Creon’s order that his name shall find no recognition or remembrance within the city. It does not matter that Polyneices lies dead outside the city walls. Exile would serve the same symbolic purpose. Associating herself with the recognition of Polyneices if not with his rebellion, Antigone suffers the same fate, despite her willingness to reason with Creon. Creon is not of a mind to be reasonable, however. He is governed by symbolic prestige and “reasons” with Antigone only so far as he hopes to be able to bring her around to his view and avoid the messy consequences of punishing a rebel. Alternatively, one loses one’s identity by allowing one’s actions to be determined by the symbolic order [Carol in [Safe]]. One becomes a mere functionary, a replaceable gear in the representations and machinations of the symbolic. So far as identity is concerned, it doesn’t matter whether the despotism to which one lends oneself is benevolent or pernicious. One true servant of God is as good as another so long as God’s good work gets done. What is the lesson of the dilemma? It depends on the good at stake. If it is simply one’s own good that is considered, Lacan argues that one must learn to divide oneself, to lend a limb or member to the projects of the symbolic order while devising a secret affair, a project (with some others) in which one can find an authentic joy and confirmation of self (FFC, Seminar II, sessions on Poe’s “The Purloined Letter,” revised and amplified later for Écrits). The humane purpose of psychoanalysis is thus, for Lacan, to help a person come to see a way of occupying this difficult middle, to see a potential in what one’s situation makes possible projected within but not primarily according to what the symbolic ordains. In this way one may both evade symbolic death and be true to one’s desire. Antigone is sublimely beautiful but her self-sacrifice is not to be held up as an example (Seminar VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis). Thus, Lacan effectively separates himself from the Sartrean view that authentic freedom demands that one recreate the world in one’s own terms, assume the burden of being God, even if suicide is the way one accomplishes this ( Essays in Existentialism, Part I). The problem with this compromise solution to the dilemma is nicely told by Slavoj Zizek in an interview with Peter Canning. It concerns the political good, the good that lies outside of what one can manage within the cracks of the symbolic order:

"In Czechoslovakia the big opposition, for example, was Milan Kundera versus Vaclav Havel. Kundera was perceived as having this cynical antistate (sic) disposition--for him, the privacy that was left you by the communist regime was the basis for opposition. Havel, of course, was the opposite. In one of his most famous stories, he takes a very Althusserian example, that of a small-time boss who owns a little grocery. Privately this character always speaks against the regime, but on the 1st of May he decorates his shop with the communist slogans. To put it in Althusserian terms, he obeys the ritual, the practices. Havel's whole point was that private disobedience coupled with public obedience is precisely the way the system functioned--that there is not only nothing subversive in this Kundera-like private space, but that the ideal subject of real socialism was precisely the one who did not believe in the system, who had this distance built in. So the truly heroic thing to do was not to tell dirty stories, but to publicly do some small thing that perturbed the ritual." (Artforum interview with Peter Canning):===>The sublime theorist of Slovenia

End [of interpretative riot collage]

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home